That’s right–I’m finally getting to my Queering the Canon project. As I mentioned some time ago, in the many years since releasing Gay Pride & Prejudice, I’ve often contemplated turning my gay eye on other Western Classics. First on my list has always been Jane Austen’s Emma, due to the homoerotic subtext that’s so obvious that more than one straight white male critic in the 20th century noticed. Feminists in general and lesbian feminists in particular have long celebrated Austen’s exploration of female friendship, and Emma offers so many different meditations on female friendship that shaping a queer variation requires very little work indeed.

As I wrote on Patreon recently, I’ve received a fair amount of negative reaction to Gay Pride & Prejudice over the years, specifically regarding my choice to edit Austen’s original text to make it gay rather than penning an original variation from scratch. I understand the criticism, but I’ve chosen this approach because I want queer classics, not just queer novels. A few reviews on Goodreads called my approach “lazy” for “switching the words around and nothing else,” which is actually a backhanded compliment–I added 10,000+ new words to the original text of P&P, and apparently these reviewers couldn’t tell the difference between Austen’s writing and mine, heheh. All kidding aside, they are welcome to their opinion. I still want a queer Austen novel, not a Kate-Christie-writing-a-queer-variation-on-Austen novel, so that’s still my approach here as well. Thank goodness Miss Austen’s works are in the public domain.

That said, I am making more changes to her wonderful text this time around. In a Patreon post titled “Queering the Canon: The (Un)likability of Emma,” I wrote at length about my writing conundrum with Emma–how Austen deliberately wrote her titular character as unlikable, and how I’d rather have a version of Emma who is less spoiled and more empathetic, given the dearth of queer classics that feature a positive storyline. (I’m looking at you, The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Well of Loneliness.) No doubt that will annoy more readers, in which case they are welcome to write the book they’d like to read, just as I’m doing.

I had intended to revise Emma several years ago, after I finished the fifth book of Girls of Summer, in fact. But then my mother decided she was ready to die, and the pandemic started within weeks of her passing, and all of my careful plans spun out of control. Instead of a sapphic variation on Emma, I wrote a different form of fan fiction, borrowing elements of Supergirl to create my take on an all-powerful, basically immortal (and immune to all forms of disease) lesbian superhero from another planet, AKA Galaxy Girl. I also wrote book six of Girls of Summer; The VSED Handbook, a mash-up between a practical guide to voluntarily stopping eating and drinking and a memoir of my mother’s choice to VSED rather than die slowly from dementia; and (most recently) a fluffy holiday short, ‘Tis the Off-Season: Book 6.5 of Girls of Summer. Grief took me in different directions than I’d planned, but while I might not have been actively working on Queering the Canon, the project was still there at the back of my mind.

Now, finally, it’s at the forefront of my mind and list of projects. Below is the cover for my upcoming variation, titled Emma: The Nature of a Lady. While I don’t have an exact release date, it should be out in the next couple of months, barring any scheduling changes.

Back in Austen’s England, the categories “heterosexual” and “homosexual” didn’t exist. Instead, pejorative nicknames like “Tommy” and “Molly” were tossed about, and euphemisms about a person’s “nature” abounded. Queer people still existed and acted on their same-sex desires, as Anne Lister and others have proven without a doubt, but in a culture where even a hint of heterosexual impropriety could ruin a gentleman or lady’s reputation, illegal gay acts were punishable by death. Much easier to go along with the status quo than to risk ruin, imprisonment, and even death by revealing your true nature.

That’s why I’ve taken it upon myself to write queer people into historical literary classics. British culture in Austen’s time was so virulently anti-LGBTQ+ that mainstream writers who wanted to sell their books couldn’t even think about penning tales of “unnatural perversion,” let alone stories that featured happy queer people. Actually, even when I was starting out as a writer in the 1990s, nearly two hundred years after Jane Austen began publishing her work, the general consensus was that you didn’t write about queer people if you wanted to sell books. Which, fine. But at this point, I’ve sold more than 40,000 copies of my queer books–including 3,200 copies of Gay Pride & Prejudice–so apparently someone wants to read them.

That’s not why I write, though. I mean, selling books is part of the business, but it’s not a motivating factor for me. I write because I enjoy it and because I would probably, most definitely go a little crazy if I didn’t. If my books find readers who are entertained, I’m happy. If they touch people’s hearts or give them a mental break from the craziness of our current world, even better. Either way, I’ll keep writing, and I’ll keep choosing to write about queer people because doing so is still a political act, even now.

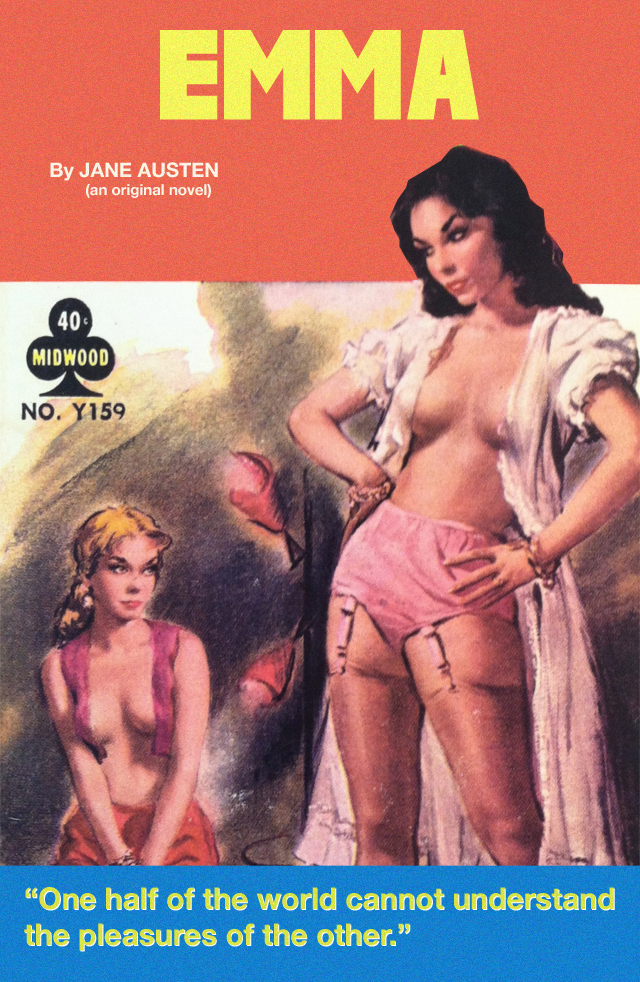

But let’s end on a lighter note, shall we? I know our dear avoidant Emma would certainly prefer that be the case. Speaking of queer Austen takes, Autostraddle, one of my favorite media sites, once reimagined Austen books through a sapphic lens with covers modeled after lesbian pulp fiction books of the 1950s. The hilarious post Every Jane Austen Novel If They Were Gay and Also Historically Inaccurate is accompanied by brief textual descriptions that are absolutely worth reading, especially Mansfield Park in which “[i]nsufferable uptight raw vegan Fanny Price has been raised by her rich aunt and uncle, because her immediate family is poor and does not have the money for the Vitamix and fruit dehydrator she requires.”

At least I’m not making Emma vegan and gluten-free–although I don’t doubt that her father, the narcissistic Mr. Woodhouse, would cut gluten, soy, and other evils from his diet if he were alive now. Still, Emma: The Nature of a Lady takes place in Austen’s time, so Mr. Woodhouse will simply have to suffer through his glutenous cakes and gruel. More’s the pity, according to him.

Love that you’re doing Emma! After watching the 90’s Mansfield Park adaptation, I feel like there is plenty of room for a queering of that too, I hope you’ll tackle that too one day!